|

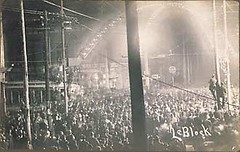

| Postcard photo of the crowd at the lynching of Jesse Washington |

Note: This post first appeared as a diary at Daily Kos on May 18, 2011. It was deleted without my knowledge, permission, or consent. It was written by me, it is my intellectual property and work product, and I retain copyright. On the penultimate day of Black History Month and a day after the second anniversary of the lynching of another seventeen-year-old Black man, Trayvon Martin, It is posted here with very minor edits.

First, a warning. What follows below the fold are very blunt, very graphic depictions and descriptions of lynching in the United States. If these depictions will cause too much distress, do not read further.

Second, an admonition. The purpose of this diary is to bear witness. It is not "violence porn" offered for prurient interest. If that is your reason for reading, please move along. I will not engage on this deadly serious topic in that manner.

Third, an apology. I have found it impossible to depersonalize this subject. What follows, then, is simply a deeply personal recording of my own attempt, now 98 years later, to remember Jesse Washington, and to accord his life and death the respect they deserve.

May 15, 1916; Waco, Texas.

I recently took a little trip — a trip back in time. Not so long ago, really. Less than a century: 98 years, to be exact. Not so far away, either, from where I live now: officially, 588 miles; as the crow flies, far fewer.

It was an ugly trip.

While looking for something else, I stumbled once again over the story of Jesse Washington. Jesse's story was one I never learned in school. Back then, at least, lynching was a subject for approximately two sentences, that ran something like this: "A long time ago, people who were prejudiced sometimes lynched people who were Negroes. It was terrible."'

There ended the lesson.

Something about the date caught my attention. May 15, 1916: 98 years ago. Still less than a century. Nizise, my father-in-law, had entered this world a month previously. My own father would not be born for more than seven years yet. My eldest uncle — the one who died in the 1919 influenza epidemic — was a few months old.

This is not ancient history. There are people still living who were alive on that day.

There are people still living who lost loved ones to lynchings.

This diary sprang from the conviction that, on this date, Jesse Washington deserved to be remembered, to have his story told to younger generations who had mostly never heard of him, amid a culture that much prefers that he remain forever forgotten. But in the process, it became clear that telling only Jesse's story would do him a grave disservice. Because his story, now officially denominated in the nation's cultural and historical zeitgesit The Waco Horror, has become limited by that name. It allows Americans to put Jesse's story in a nice tidy convenient little box of racist exceptionalism. And it was not exceptional. For far too many of Jesse's brothers and sisters and our ancestors, it was business as usual.

And so it is time to bear witness. Unflinchingly. It is time to witness this brutal and hideous "American exceptionalism" at its most basic and base; to recognize it, to name it, to call it out for what it is; to bear witness to the scars it has inflicted on what we ironically call the modern American "criminal justice system" and the people of color who disproportionately inhabit it.

It is time to see The Waco Horror in its proper context: of a piece with day-to-day life for African Americans in this young country, part and parcel of the nation founded on the twin original sins of genocide and slavery.

The American Horror.

The Waco Horror

I've been to Waco before. It's flat, dry, dusty — moreso in 1916. By this time of year, it's already cruelly hot. A merciless sun would have scorched the field laborers. The winds don't cool the sweat from your brow; they merely drive the local dirt into your skin like so much microscopic buckshot.

It's the sort of land where a single spark can turn acres into an inferno in less than a single beat of your heart.

On this date in 1916, a spark will be dropped . . . and all of Waco will be consumed in the conflagration like so much dried and rotting timber.

The spark was the death of a white woman, Mrs. Fryer. She and her husband, local white landowners, hired African American laborers to work their fields. Some five months previously, they had hired the Washington family: parents and children, including Jesse, aged seventeen. Jesse was at best illiterate; contemporaneous accounts indicated that he was also what we would today call developmentally disabled. Of course, some of those same accounts quoted white men who insisted that he was merely "lazy" and "worthless."

The Fryers seem to have had no complaints regarding the work or personal habits of the Washington family in general, or of young Jesse in particular. Not, at least, until May 15, when Mrs. Fryer turned up dead. Not merely dead, but murdered — and, if subsequent prurient allegations were to be believed, raped, as well.

Mr. Fryer called local law enforcement, who arrived on the scene and soon turned their attention to young Jesse. According to their accounts at the time, they questioned Jesse and he confessed, both to rape and to murder. However, subsequent investigators generally seemed to have concluded that 1) Jesse was incapable of understanding and making such a confession, and 2) that evidence demonstrated that Mr. Fryer committed the murder himself and sought to deflect the blame onto a young, illiterate, developmentally disabled African American itinerant laborer, knowing full well that law enforcement would be only too ready to assume the young Black man's guilt.

What happened next is difficult to read. More difficult still to write, because mere words are inadequate to the task.

The newspapers named it The Waco Horror, as though it were something unheard-of in its brutality, shockingly beyond the pale of American social norms.

It was none of those things.

Oh, it was a horror, all right, indescribable in its brutality, unfathomable in its inhumanity, unspeakable in its raw and raging blood-lust.

Once the police pointed an accusatory finger in Jesse Washington's direction, their job was done. They never needed to lift that finger — indeed, they were hardly given a chance. At that point, the Good White Men of Waco took over the task of meting out "justice." Once the word went out, it spread like wildfire amid the dry timber of the town's buildings, and homes and businesses emptied themselves of the men who jockeyed for position to be the first to bring "justice" to the hated exemplar of Depravity.

And Waco, Texas, bucolic, if dusty, ranching town, exploded in a single instant into a seething cauldron of white-hot White rage and hatred.

And these were the Good White Men of Waco: the city fathers, the deacons in the churches, the family men, the honest businessmen. The were the ordinary husbands and fathers and sons and brothers, those who ran the town and those who kept it running, all of whom undoubtedly prided themselves on their well-developed and highly civilized sense of justice.

And when, in the fullness of time, the Good White Men of Waco gathered themselves together into a mob bedecked in double-breasted coats and white boaters, they fell upon seventeen-year-old Jesse Washington, he of the illiterate mind and hated Black skin. And they seized him, and dragged him forth from the fields of the Fryer home, that they might deliver unto him the Lord's "justice."

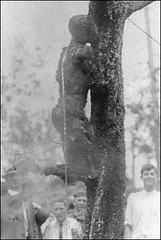

The photos look like a group of fin-de-siècle men crowding a public square on a summer's day, perhaps to listen to a political candidate or preacher, preparatory to an ice-cream social or other festive event. The event apparently was festive, but not in the usual sense of the word. Far from an al fresco celebration of a happy occasion, it was an orgy of rage and blood and pain and cruelty.

First, the mob grabbed Jesse en masse and began to beat him. They beat him with fists, with booted feet, with clubs, with stones — it made no matter, whatever was to hand or foot would, and did, suffice. Then they wrapped a heavy iron chain around his neck and dragged him from the Fryer homestead, through the stony, dusty streets of Waco, to the town center. As they dragged him, those on the mob's sidelines continued to pummel and kick his battered and broken body. Not enough to kill him, mind you; that would've been a mercy, and the Good White Men of Waco were determined to do their duty in punishing this sinner in the hands of an angry God. Mercy was undeserved, and wasted on such.

When the reached the town center, they hoisted Jesse, by the iron chain still wrapped about his neck, upon a wooden gallows — making sure all the while that the chain was not wrapped so tight as to choke him. It wouldn't do for the hated Black man, the embodiment of evil, to die before the Good White Men of Waco had administered the fullness of their angry God's justice to the sinner.

Before hoisting him, though, they stripped him naked, castrated him, and wrapped him in a white cloth. Accusatory scarlet ribbons of blood ran down his legs as they hoisted him upon the tree again, all the while making sure that the chain was not so tight as to kill him before they were ready for the bleeding and broken Black eunuch to die.

But killing alone was insufficient to expiate the mob's sins, projected onto young Jesse Washington like the scapegoat he was. The mob demanded true purification: Fire. And so a pyre was built and lit beneath the gallows, tended by those closest. One of the Good White Men of Waco assumed the responsibility for ensuring the Jesse be shriven by the cleansing flame: He raised and lowered, raised and lowered, raised and lowered the chain, repeatedly baptizing Jesse's lower extremities in the blaze, each time pulling him out of the flames before Death could claim him, over and over and over again. And Jesse, terrified, gibbering, mad with pain, repeatedly reached above his head to grab the chain, to try and hoist himself out of the consuming fire, melting the skin off his fingers . . . until the Good White Man, weary of Jesse's efforts to escape the purifying inferno, pulled out a knife and cut off Jesse's fingers.

Eventually, the mob tired of the spectacle, although whether out of some deeply buried sense of atavistic guilt or merely eagerness to see the Evil die, who can say? But finally, the chain was pulled taut, and the body consigned to the flames, and Jesse's spirit finally escaped Hell.

Eventually, the country learned what the Good White Men of Waco had done. And it professed shock, and horror, and issued impassioned pleas that such never happen again. And the newsmen of the day denominated it The Waco Horror, as though by naming it, they could somehow chain the beast that slew Jesse Washington, confine and consign it to Hell, where it could bring no more disrepute upon America's "civilized" denizens.

Of course, they failed.

Just as they had failed all of Jesse Washington's predecessors upon the tree and the pyre, just as they would fail all his successors, too.

Hanging Was the Least of It

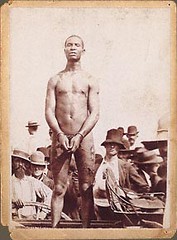

These next two photos, in some ways, cut more deeply than the images of actual burning and strangulation. No one seems to know exactly when or where they were taken. The man's name is unknown now — if indeed his own name ever was known to anyone but himself.

Stripped naked, chained at the wrists, whipped raw and bloody, front and back, and put on display by the Good White Men of his town as they wheel him to his fate, he stands tall, strong, gaze unflinching, unbowed and apparently unbroken by their best efforts at torture and shame. He reminds me of the warriors among my Red ancestors: proud; secure in himself; unwilling to cede even a millimeter of his spirit to those who would destroy his body.

Of course, beyond the obvious inference that this man was eventually hanged, we don't know how his life ended. We don't know whether he maintained the iron composure we see here, or whether the torture and pain finally got to be too much. What we do know is that what we were taught in school — that "lynching" meant "hanging" — was actually the least of the process, and usually merciful by the time it finally occurred.

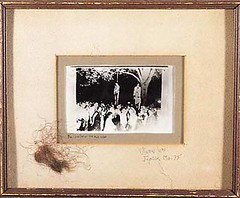

Among their other base and brutal motivations, lynch mobs were commonly driven by the need to humiliate: to strip the victim bare both literally and figuratively, leaving him (and sometimes her) without a shred of dignity, respect, or bodily integrity. Mobs routinely claimed trophies, as in a noted case from Indiana, long a hotbed of Klan activity. In Marion, the mob took a trophy from Messrs. Shipp and Smith: hair, cut from one of the victim's heads, and tucked under the glass of a signed and framed photo of the event. In Coatesville, Pennsylvania, young White boys and their fathers cut charred fingers and toes, flesh and bone, from the burned body of Zack Walker, then repaired to the local candy company for refreshment.

It's a dynamic common to serial killers, made acceptable — nay, desirable — here by the consent and endorsement of the mob.

Of course, a piece of the actual body was not required; the photos themselves often sufficed as trophies. The mobs often posed the bodies after death, then stood over their victims looking like nothing so much as big game hunters posed triumphantly over

their kills, awaiting the congratulatory camera flash.

In Pound Gap, Kentucky, the Good White Men flung Leonard Woods's body to the deck beneath their feet so that they could be photographed with their prize: a lynched African American man. The Good White Men of Gadsden, Alabama, cut down Bunk Richardson's body, then propped it up against the railing and held it there so that photos could be taken, turned into postcards, and sold and sent through the mail, cementing their place in the event for posterity.

In Pound Gap, Kentucky, the Good White Men flung Leonard Woods's body to the deck beneath their feet so that they could be photographed with their prize: a lynched African American man. The Good White Men of Gadsden, Alabama, cut down Bunk Richardson's body, then propped it up against the railing and held it there so that photos could be taken, turned into postcards, and sold and sent through the mail, cementing their place in the event for posterity.

Indeed, the practice of turning lynching photos into postcards became a full-fledged American pop-cultural phenomenon of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. The cards were sent through the mail, often by attendees at the lynchings, proudly announcing their participation; sold door-to-door and in shops, both as commemorative items and for sales inherent in their titillation value; and collected and traded like baseball cards, by children and adults alike.

Sexualization, Mortification, Purification

American strains of Christianity, whether puritanical Protestantism or penitential Catholicism, have always contained strong undercurrents of sexual repression and mortification. Combined with racial hatred, fear, and persecution, it created a poisonous brew of race-based sexual paranoia. Black women were demonized as loose and lewd, allowing upstanding "Christian" men to justify their rape of slaves and servants. Black men, on the other hand, were demonized as sexual savages, enslaved by their basest desires and always looking for an opportunity to rape "pure" White women. Punishment of such conduct was an issue not merely of criminal justice, but of Christian duty.

It was also a good way to cover up one's own crimes.

Throughout "American" history, men of color routinely have been falsely accused of the rape of white women. But during the heyday of the lynching era, "rape" wasn't even a necessary condition for stringing up a Black man. Vague allusions of sexualized assault would do. So would speaking to or leering at a White woman — or even merely looking a White woman in the eye. So would nothing at all. Sometimes, all that was needed was the fact that a Black man breathed.

But this hypersexualization allowed for the addition of a particularly bloody and brutal element to many lynchings: Castration. And during a lynching, castration was carried out in toto, without benefit of anaesthetic, and always prior to the actual hanging. After all, what better way to humiliate a man thoroughly than to emasculate him, literally and publicly, for all to see?

And when I say for all to see, I mean all. A lynching in Ruston, Louisiana, is instructive. A Black man, accused of rape, was stripped — but only from the waist down. He was castrated, then a a piece of fabric was wrapped around the front of his lower body in a display of false and hypocritical mob modesty. Only then was he hoisted from a tree limb and strangled. And the Good White Men and Women of Ruston who came to view the spectacle brought their children.

That which is soiled must be purified. Perhaps nowhere in our culture is that more true than where the "soiling" in question is putatively sexual. And so, in the fullness of time, after the Good White Men had removed the sexual danger the Black man posed to the Good White Women via castration, they delivered him unto the flames.

And so, the pyre. Summoning echoes of European and early American religious persecution, mobs often literally burned their victims at the stake. In Georgia, a photographer memorialized the burning of lynching victim, the crowd watching his charred body swing from the gallows — though no one could be bothered to record his name. The photo was turned into a postcard, actually sent through the mail, with a message on the back.

The text of the handwritten message:

Warning

The answer of the Anglo-Saxon race to black brutes who would attack the womanhood of the south.

In Texas, a crowd of adults and children surrounds the smoldering remains of an unidentified lynching victim. And a denizen of Anadarko, Oklahoma, proudly preserved for posterity a photo of Bennie Simmons, whose body was soaked in oil and set afire while he was still alive.

And in Durant, Oklahoma, a mob celebrated what became known as the Burning of John Lee. Mr. Lee, accused of multiple crimes, including the alleged shooting of a White woman, was killed by gunfire at the hands of a "posse." His death, however, was apparently insufficient to sate the mob's desire for vengeance, and a pyre was constructed, his body placed upon it, and the remains set aflame. Afterward, the White citizens of Durant rampaged through the "'colored" sections of Durant, turning it into a literal sundown town, warning Black residents that any of them found within the town limits after sunset would be killed.

Heartland Horrors

Of course, it's easy to dismiss Texas as part of the so-called "Old South." Such horrors are assumed, even today, to have been confined to the states south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

Think again.

In Minnesota — about as far to the North as it gets without leaving the country — Elias Clayton, 19, Elmer Jackson, 19, and Isaac McGhie, 20, would beg to differ with you. That is, they would, had they not been lynched by a mob in downtown Duluth after being falsely accused of raping a White woman.

Then there's Cairo, Illinois. You may remember hearing the town's name; it's been in the news again in recent years. Why? Because Republican Missouri State House Speaker Steve Tilley, when asked which he'd rather see "underwater," Missouri farmlands or the Cairo homes of poor African American families, responded: "Cairo. I've been there, trust me. Cairo. Have you been there? Ok, then you know what I'm saying then." Majority African American, Cairo has a long history of racial unrest, including a three-day race riot in 1967 following the death of an African American soldier home on leave.

But Cairo's terrible racial history goes back much further than 1967. On the night of November 11, 1909, the Good White Men and Women (reportedly some 500 women, as a matter of fact) of Cairo turned out for an event held under the relatively new-fangled electric lights that set off the downtown arch. An event that would put that arch to practical, not merely aesthetic, use. A brightly-lit arch suitable for lynching a Black man accused of murdering a White woman.

At left, obviously, is Mr. James's portrait in better days. At right? While it's impossible to tell what the charred and bloated lump atop the pole is from the photo, it's actually what remained of Mr. James's head, after the mob burned him. They mounted the head on a makeshift pike in the center of town, a [then-]modern version of a medieval castle wall.

The lynching whipped the mob into such a frenzy that, after Mr. James was thoroughly dead, they broke into the town jail, seized a White man accused of murdering his wife, and hanged him, too.

In the dawn's early (natural) light, local boys then had their photo taken standing triumphantly over a grisly trophy in the street below: the ashes of Mr. James's charred body and bones. The photos shown here were part of a series of fifteen that were turned into collectible postcards.

And some of the country's most brutal lynchings occurred smack in the center of America's so-called heartland. Nebraska hosted a number of such "events" over the years, including the one that produced one of the most horrific — and horrifically iconic — of all the lynching photos, that of William Brown of Omaha.

Brown had been arrested and accused of molesting a White girl. On September 28, 1919, the Good White Men of Omaha stormed the jail, very nearly lynched the town's (White) mayor for urging them to disperse, and seized Mr. Brown, torching the courthouse in their wake. They hanged William Brown from a town lamppost, castrated him, shot him, and then set his body afire. When all was said and done, troops were required to restore the peace, and four additional persons were killed and another fifty wounded in the rampage. The photo of the incineration of Mr. Brown's body in the collective face of a smug and sated mob was sold as a souvenir.

American Horror

Young Jesse Washington's charred and mutilated corpse casts a dark shadow — but it is dwarfed by the shadow of the beast that slew him that day in May, 1916. It is a shadow that darkens the lives and futures of people of color in this country, even today. The beast is not dead; it merely slumbers most of the time. Occasionally, it awakens, and devours yet another Black man, grinding flesh and bone and blood and soul in its jaws. Today, of course, the beast often takes a different form: blue uniforms and cherry-topped cars and metal bracelets; dark suits and robes in antiseptic courtrooms; stone benches and steel toilets caged by iron bars. Today, we call it The System, and we beat our metaphorical breasts about how bad it is, and wish that someone would Do Something . . . and then we go on about our lives. And every day, another descendant of Jesse Washington becomes trapped in its maw.

Yes, it's a horrific sight. But look. Look long and hard. Because this — THIS is the legacy of America's original sins, of slavery, of the Klan and the Nightriders, of Jim Crow. This is what we do to our own citizens.

Look. Feel. Grieve. Remember. Act.

Ninety-eight years after this day, we owe that much, at least, to Jesse Washington. And we owe much more to his descendants. We owe it to them, at long last, to make this right.

Epilogue

First, and I'm going to say this straight out: This is why it's inappropriate to use the word "lynching" for anything less than what you see here. This is why it's inappropriate to discuss hanging, or tying, or burning, or castration in reference to African Americans. Yes, it's true: There are some things you don't get to say unopposed.

Osama bin Laden was not lynched. Ultra-right-wing judicial nominees like Thomas and Pickering, forced to bear minimal scrutiny for racist attitudes and behaviors, are not lynched. Professional athletes disciplined for bad behavior are not lynched.

And each and every time I see this kind of racist false equivalence, I'm going to call it out. I hope you will, too.

Second, as I indicated in the Introduction, this was not intended to be a research piece, nor reporting. Yes, ultimately, there was a public outcry of sorts against The Waco Horror. Over the years, there have even been investigations. More recently, there have been reconciliation attempts, although I'm not sure I'd call them a great success. If you'd like to know more about those topics, I suggest the following sources:

Nieman Reports: Brent Staples, The Perils of Growing Comfortable with Evil.

Copyright Ajijaakwe, 2011, 2014; all rights reserved.

Copyright Ajijaakwe, 2011, 2014; all rights reserved.

It took me a while to get through this, it was difficult to read. I only received the 'sanitized' explanation of lynching in school, and while that was bad, I'm appalled at just how much worse it actually was. Thank you for the education.

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome, hon. And I know what you mean. In trying to write it years ago, it took me several false starts because it was just so horrifying. And I already KNEW the story. Once I got under way, though, IIRC, I did it pretty much straight through, probably so I wouldn't have to return to that place. But it's one of those things that we all need to know. We owe Mr. Washington (and all the others) that much, I think.

ReplyDeleteI will never be the same. Life changing article. Thank you for the brutal honesty. I had to stop reading it several times as my tears blurred my vision and the lump in my throat made it difficult to breathe.

ReplyDeleteI will never be the same. Life changing article. Thank you for the brutal honesty. I had to stop reading it several times as my tears blurred my vision and the lump in my throat made it difficult to breathe.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Believe me, I wrote this in stages - many of them - because I had the same problem. It was extraordinarily difficult to write, but it needed to be done. And Jesse Washington (and all the many others, including those whose names we will never know) deserves our tears - and our commitment to change.

DeleteThank you. Believe me, I wrote this in stages - many of them - because I had the same problem. It was extraordinarily difficult to write, but it needed to be done. And Jesse Washington (and all the many others, including those whose names we will never know) deserves our tears - and our commitment to change.

Delete