Those of us of mixed race are often told we're "not." Not one race or another. Not "mixed race," because that's not a thing. Not a member of any group, or community, or culture, because we're not enough of anything for some, and too much of other things for the rest.

Those of us of mixed race are often told we're "not." Not one race or another. Not "mixed race," because that's not a thing. Not a member of any group, or community, or culture, because we're not enough of anything for some, and too much of other things for the rest.Recently, I've been hearing a revival of the trope that there are no Black Indians. That is, if you're Black, you can't also be Indian; if you're Indian, you're not Black. Never mind what your DNA is; you have to be one or the other. [And I'm hardly the only one who's been hearing this; my Spirit Sister, who has my same tri-racial make-up in different proportions, is actually the one who suggested I write this.]

As a practical matter, most people are forced to choose. We then often must construct our own identities: ones that don't fit into societally-approved categories, but rather, live in the interstices, yet encompass who we are fundamentally. Such was ultimately the case with one of this country's most famous Black Indians - and neither ethnic group can afford to forget his contributions to our collective history.

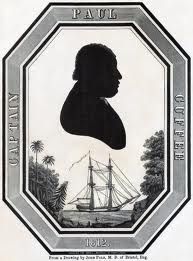

Below the jump, a Black History Month reminder of the man who was Captain Paul Cuffee.

CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY

Born January 17, 1759, on Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts, to a Black freedman and an Indian woman, Paul Cuffee was self-made in ways that many today could never fathom. Of two races and two cultures, both splintered and diluted by the powers of colonialism, he was forced to [re]construct for himself his very identity.

His father was known as Cuffee Slocum. In actuality, his name was Kofi, an African name not uncommon in what is now known as Ghana. Mr. Slocum was Asante by ethnicity (Ashanti, the modern corruption of the word, is more commonly used today). At age 10, Kofi was captured by slavers and in 1728 brought forcibly from Africa to Newport, in the British colony of Rhode Island, where he was bought by (or given as a gift or part of a wedding dowry to) a white colonist from Dartmouth, Massachusetts, one Ebenezer Slocum. Fourteen years later, on February 16, 1742, Ebenezer Slocum sold Kofi to his nephew, John Slocum. Documents of sale list Kofi as "about 25" years of age; the purchase price for this young man was £150 Sterling.

Like his uncle, John Slocum was also a Quaker, and the Dartmouth Society of Friends maintained close ties to the nearby Nantucket Society. In 1733, the Nantucket Quakers became the first Society of Friends in the British colonies to denounce slavery. It appears that this decision had a profound influence on members of the Dartmouth congregation, including John Slocum: Within a relatively short period of time after purchasing Kofi, Slocum reportedly concluded that owning slaves was incompatible with his religious beliefs, and freed him - although not, apparently, with any financial or other resources to help him survive. There are reports that John Slocum allowed Kofi to work as a laborer for wages thereafter. In need of two names, Kofi kept his own name, which had been corrupted by colonists into "Cuffee," as first name, and took Slocum's surname as his own last name.

In 1746, Cuffee Slocum married Ruth Moses, a Wampanoag Indian [from the same Algonquin root as my own language, literally, Waabaanoowag, People of the East or People of the Dawn] of the local Aquinnah community. They had ten children, all "free-born," and Mr. Slocum raised them in the Quaker belief system of his former "owner." Mr. Slocum taught himself to read and write (including teaching himself the Scriptures used in the Quaker services) while working as a fisherman, a farmer, and a carpenter. In 1766, when seventh child Paul was seven years old, Mr. and Mrs. Slocum bought a farm on 116 acres of land in the area of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Paul was raised to help run the farm, and took over operations in 1772, at age thirteen, when his father died.

In the meantime, it appears that Paul's strong sense of identity and independence was already asserting itself. By 1778, when he was nineteen, he had jettisoned the surname of his father's "owner," preferring instead to take his father's first name as his own family name. He reportedly convinced all of his siblings save the youngest, Freelove, to do likewise, and prior to their mother's death in 1787, his identity as free man Paul Cuffee was well and solidly established.

CONSTRUCTING A MARINEER

Some accounts indicate that, before his death, Kofi Slocum had taught his son the alphabet; whether Paul had already learned to read by this point is unclear. But like his father, young Paul was determined to pursue an education for himself, and a career that would better his (and his family's) lot in life, and apparently from a very young age worked hard at both labor and letters to that end. Living near New Bedford, Massachusetts - what was, at the time, the heart of the colonies' whaling industry - gave him access to sailors, and from them he reportedly learned all he could from the vantage of the shore about both ships and sailing. At age 16, he signed with the crew of a whaler; from there he moved to cargo ships, where he learned navigation skills. He kept a journal during his voyages, and in it, he referred to himself as a marineer, presumably (as was common in those days in every context) an alternate spelling of mariner. At the outset of the Revolutionary War in 1776, when Paul was seventeen, the ship on which he served was captured by the British, and he was held prisoner for three months. Upon his release, he returned home to work the family farm, where he resumed studying and saving.

CONSTRUCTING A CAPTAIN

"Captain" is one of those words that is and was heavily weighted with the trappings of command - authority, power, both over others and over one's own destiny. It was a remarkable aspiration for a young Black Indian in the days before the country was even a country - and even more remarkable that he achieved it, in the face of odds that probably would have defeated even most young white working class men of the time.

"Captain" is one of those words that is and was heavily weighted with the trappings of command - authority, power, both over others and over one's own destiny. It was a remarkable aspiration for a young Black Indian in the days before the country was even a country - and even more remarkable that he achieved it, in the face of odds that probably would have defeated even most young white working class men of the time.After spending time serving as a marineer on various ships, and as a prisoner of war for that service, Paul Cuffee knew what he wanted to do and who he wanted to be: Captain Paul Cuffee, businessman and shipping magnate. And so, in 1779, at age twenty, he began. He and his brother David built their own small cargo ship to trade around the islands in the immediate area. Later that year, on a solo cargo run to Nantucket, he was attacked by pirates - the first of several such incidents that Paul would survive.

Eventually, however, one of his Nantucket voyages would be profitable, and he never looked back. He bought a second ship ad hired crew to run it. He worked and saved and eventually was able to expand his empire from two ships to a fleet, then commissioned the building of his first closed-deck ship (the Box Iron, which weighed some 14-15 tons), then commissioned the building of a schooner (some 18-20 tons). By the end of the 1780s, Captain Cuffee's fleet was led by the flagship Sun Fish, a 25-ton schooner, which was later supplanted by the 40-ton schooner Mary. By now, he had his own Westport shipyard, and in 1795, he sold both schooners to finance the building of a new, even larger flagship, the 69-ton Ranger, which he launched the following year.

Three years later, in 1799, he bought a 140-acre waterfront property in Westport for $3,500. In 1800, he bought a half-interest in the Hero, a 162-ton barque (a three-mast sailing ship). Six years later, he oversaw the construction of both his favorite ship, a 129-ton brig (a sailing ship with dual square-rigged masts) that he named Traveller, and his largest ship, the aptly-named Alpha, weighing in at 268 tons.

By this point, Captain Cuffee was one of the wealthiest - perhaps the wealthiest of - men in the country of either Black or Indian ancestry.

CONSTRUCTING A LEADER

It appears from the historical record that Captain Cuffee maintained at least some ties with the Wampanoag community of his mother's family. At a minimum, he expanded the ties of his own family: On February 25, 1783, when he was twenty-four, he married Alice Pequit, a Wampanoag Indian from the same Aquinnah community as his mother. Together, they moved to Westport, Massachusetts, where both his shipyard and his family homestead would eventually be located, and they raised seven children. It may be that his new family fed Captain Cuffee's future activism, but the seeds were already firmly planted - and, in fact, already bearing fruit.

Three years earlier, when he was twenty-one, Paul Cuffee did the unthinkable, for either a Black man or an Indian: He openly defied Massachusetts law, refusing to pay taxes on grounds that Black men, even free-born Black men, were denied the vote. Tha same year, he formally petitioned his local government of Bristol County, demanding an end to taxation without representation for free-born Black Americans. The petition was, of course, denied - but it helped to lay the foundation for the Massachusetts legislature's decision, later that year, to grant voting rights to all free-born citizens of the state. Male citizens, of course. Non-Indian citizens.

Meanwhile, it was becoming ever more apparent to Captain Cuffee that, free-born or no, wealthy or no, Black Americans would not be afforded the same status, privileges, or lives generally as their white counterparts. More, their very presence was not even welcome - unless, of course, that presence existed to serve white masters. A movement was already afoot among the nascent country's white leadership, including such luminaries as Jefferson and Madison, a movement supported philosophically even by many of the at least nominally abolitionist groups such as the Society of Friends, to rid the country of Black residents. Oh, it was often not put quite so baldly, couched rather in terms of "resettlement," of "colonizing" Black people elsewhere (i.e., "back in Africa"). But for the free-born Black Americans of the time, it meant exile from the only land they had ever known.

Paul Cuffee decided to embrace it.

For years, the British had been trying to colonize parts of Africa, particularly Sierra Leone. In 1792, 300 years after the first Europeans invaded these shores with colonial aspirations, British abolitionists founded the Sierra Leone Company, England's second venture into colonizing Africa with resettled Black residents. The first, in 1787, was the St. George's Bay Company, founded to resettle England's so-called "Black Poor" in Africa. The endeavor included 300 Black men and women, plus an additional 111 white Englishmen and and -women sent to "'assist" in creating a society. The venture was spectacularly unsuccessful, partly due to disease and abandonment by the intended colonizers, and partly to having been burned to the ground as collateral damage in a conflict between indigenous Temne villagers and slavers.

The Sierra Leone Company fared somewhat better, but it, too, did not survive in its initial form. The effort was propelled by British abolitionist Granville Sharp, who insisted that its purposes were entirely to promote the general welfare: both of former slaves who would be resettled as free men on their "own" continent (nonetheless to be known as the Free English Territory of AFRICA], and of the British Crown, which would obtain manufacturing, trade, and other advantages. In a word, classic colonialism, despite the absence of overt enslavement. Nonetheless, a coalition gradually took shape, comprising a number of British political leaders, abolitionists on two continents, and slaves freed during the American Revolutionary War and temporarily resettled in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In 1792, abolitionist John Clarkson led an expedition of some 1,100 of the so-called "Nova Scotian Settlers" from Halifax to the newly-established colony of Freetown, Sierra Leone. Like its predecessor, however, Freetown was burned to the ground, this time by the French during the wars between France and Great Britain. This time, however, the survivors rebuilt, and the Sierra Leone Company was itself succeeded by a new group, the African Institution.

The African Institution was established in 1807, after Great Britain had finally abolished slavery. Headed by the Duke of Gloucester (nephew of King George III), the new organization had leaders and allies with real political power in England. Ostensibly, the first goal of the African Institution was to raise the standard of living of the Black residents of Freetown - a goal belied by the monopoly status England afforded to white British merchants at the expense of the Black merchants who actually lived in Freetown.

Captain Cuffee had been following developments in Sierra Leone with interest, and had been in contact with members of various American chapters of the African Institution, who sought his help in making the Sierra Leone colony viable. After considering the options for two years, he decided in 1809 that the time was ripe to intervene.

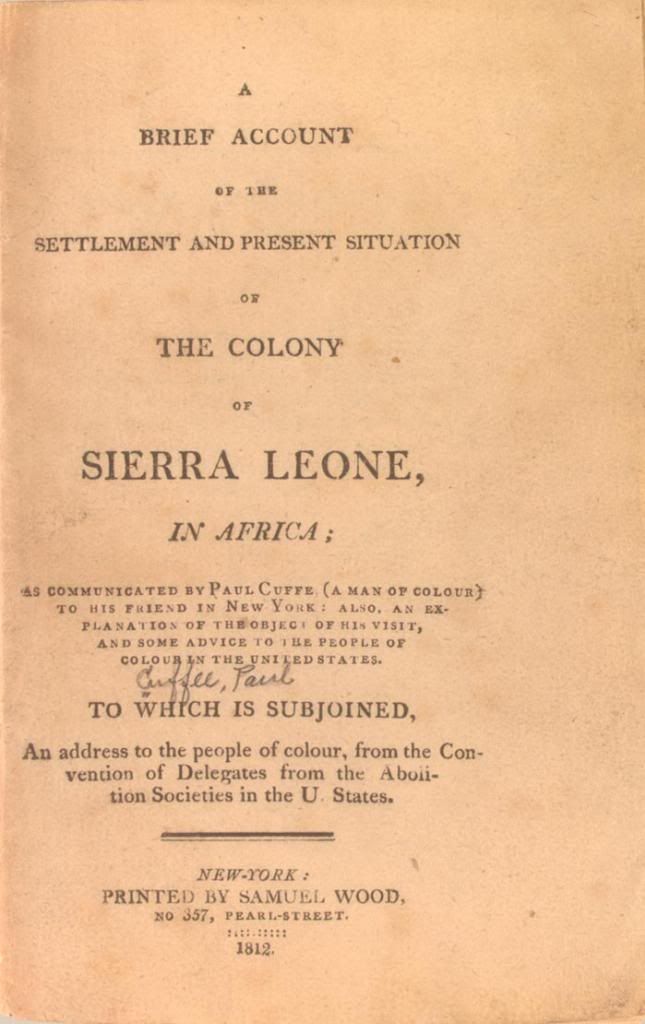

On December 27, 1810, Captain Cuffee set out for Sierra Leone, arriving in Freetown on March 1 of the following year. He met with immediate opposition from British colony leaders who resented the possibility of American competition with British goods and services. His own attempts at selling trade goods there did not succeed, either; British tariffs on imports were too high to make them affordable for Freetown citizens. It was, however, a quick and thorough education on the problems presented by British monopolistic practices, and on April 7, 1811, he met with Freetown's foremost Black business leaders to ascertain their needs. Jointly, these leaders and Captain Cuffee submitted a letter to the African Institution outlining those needs, which they identified as settlers to work in three specific growth areas - whaling, farming, and as merchants. The African Institution was receptive to their request, and Paul Cuffee and the Freetown merchants subsequently founded a mutual-aid society for the merchants, the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone. The Society's given mission was advance the merchants' trade interests; the subtextual mission was to break England's monopoly system. To that end, Captain Cuffee sailed for Great Britain, docking in Liverpool in July, 1811, then traveling on to London. There he met with African Institution members, secured both additional monies for the Friendly Society and permission from the British government to continue his efforts in Sierra Leone, and then returned to Sierra Leone to strategize further with the Friendly Society membership before heading home to the United States.

However, with the next round of hostilities between the United States and Great Britain already in the offing, the political climate had changed during Captain Cuffee's absence. The U.S. had placed an embargo on the import of all British goods, and the Captain's ship, Traveller, was caught in the embargo's net, seized along with all its cargo by Customs officials.

Stymied in his attempts to secure release of his cargo, Captain Cuffee appealed to officials in Washington, D.C. - first to Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, and then straight to President James Madison. He reportedly was "warmly welcomed" to the White House by President Madison, who, after discussing the situation and concluding that Captain Cuffee had no intent to violate the pre-war embargo, personally ordered the return of his cargo. Madison also used the meeting as an opportunity to learn more about Africa in general and Sierra Leone in particular, although he ultimately rejected the Captain's request for aid for the resettlement colony in Sierra Leone. Despite that rejection, Madison reportedly regarded Captain Cuffee as an authority - perhaps the authority - on Africa.

CONSTRUCTING A ROLE MODEL

Captain Cuffee had intended to travel regularly between the U.S. and Sierra Leone in support of the Freetown colonization effort, but the War of 1812 intervened. War presented difficulties for Paul Cuffee on several fronts: in very practical financial terms, because it halted all trade between the U.S. and Sierra Leone; in political terms, because it prevented him from aiding in the settlement of free Black men and women in their own country; and in philosophical terms, because the war itself violated the tenets of peaceful resolution of his Quaker spiritual teachings.

Captain Cuffee had intended to travel regularly between the U.S. and Sierra Leone in support of the Freetown colonization effort, but the War of 1812 intervened. War presented difficulties for Paul Cuffee on several fronts: in very practical financial terms, because it halted all trade between the U.S. and Sierra Leone; in political terms, because it prevented him from aiding in the settlement of free Black men and women in their own country; and in philosophical terms, because the war itself violated the tenets of peaceful resolution of his Quaker spiritual teachings.Never one to sit idly by, he began by using his status as an international shipping magnate, well known to the leaders of both countries, to convince them to resolve their differences peacefully. His efforts failed, of course, but he kept his larger goal firmly in sight, and began rounds of meetings with groups of free Black citizens along the Atlantic Seaboard. He used these presentations to encourage Black Americans to relocate to Sierra Leone after the war's end, and to work in the meantime to aid the colonization effort. He published a pamphlet about the colonization project. And through it all, he continued to follow his faith, becoming, in 1813, the largest single donor to the construction of the new Society of Friends Meeting House in his hometown of Westport, Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, between the war and mismanagement by a business partner, he sustained significant financial losses. When the War of 1812 ended in the Treaty of Ghent of 1814, he was not yet in a position to return immediately to Sierra Leone. at the end of the following year, however, he was able to mount another expedition.

On December 10, 1815, Captain Cuffee set sail from Westport, leading a group of free Black persons, 18 adults and 20 children (aged 8 months to 60 years old), along with equipment for building a saw mill upon arrival. At least some of the passengers paid a fare of some amount, and a citizen from New Bedford donated $1,000 toward the expedition. Captain Cuffee paid the remaining costs, more than $4,000 at the time, out of his own pocket. Roughly two months later, on February 3, 1816, the group arrived at Sierra Leone.

His welcome was a bit less warm this time, unfortunately. During his absence, the British government had instituted a requirement of a loyalty oath to the British Crown, something many settlers distrusted out of fear that it would lead to their military conscription. Continued economic difficulties likewise contributed to unrest, and an accompanying distrust of the prospect of immigrating new colonists. Captain Cuffee took significant losses on his trade goods. Ultimately, however, all 38 colonists were settled in Freetown, and the Captain could regard the venture as an expensive success. He provided for the first year's worth of provisions for each of the 38 colonists he brought with him, and those costs, combined with substantial tariffs, left him with a deficit of more than $8,000. The African Institution, so eager for Captain Cuffee's help, contributed not so much as a shilling to the venture.

By his return to the U.S. in 1816, he had developed a vision of a mass emigration by free Black Americans to Sierra Leone (and possibly to Haiti, newly governed by free Black leaders). He sought funding from Congress, which was denied, but Black Americans began to evince interest in the idea, and many white Americans thought it a convenient solution to troublesome problems of race in the nascent country. Members of the newly-formed Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, led by ministers Robert Finlay and Samuel J. Mills, convinced Captain Cuffee to join them in their own efforts to establish African colonies for "repatriated" Black Americans. However, faced with the virulent racism of many of the Society's members, particularly those like Henry Clay whose primary interest was in shoring up the slave system in the American South, the Captain soon abandoned that partnership. The Society continued to push for Black resettlement in Africa, often by force. Its efforts, combined with those of British colonialism, did much to set a long-term course for modern political and humanitarian crises in places like Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Captain Cuffee, meanwhile, faced declining health. He did not know it at the time, but his one expedition to resettle 38 free Black men, women, and children in Freetown would be his final trip to Africa. His spirit left his body on September 7, 1817, at the too-young age of 58. In fewer than six decades, this free-born Black Indian man present at the creation of one new country, who helped to found the settlement of another, accomplished more than most people, historical or contemporary, could ever dream of doing.

Captain Cuffee, meanwhile, faced declining health. He did not know it at the time, but his one expedition to resettle 38 free Black men, women, and children in Freetown would be his final trip to Africa. His spirit left his body on September 7, 1817, at the too-young age of 58. In fewer than six decades, this free-born Black Indian man present at the creation of one new country, who helped to found the settlement of another, accomplished more than most people, historical or contemporary, could ever dream of doing.His legacy lives on, nearly 200 years later, in the school that bears his name: The Paul Cuffee School of Providence, Rhode Island. It bills itself as "A Maritime Charter School for Providence Youth," and it serves a diverse population, including children of color who would otherwise have no access to the maritime tradition. Divided into three sections - "Lower School," "Middle School," and "Upper School" - it provides a K-12 public-school curriculum built around a maritime theme that infuses the entire educational experience, from history to hard sciences to physical fitness.

It also lives on at Bridgewater State University, where Captain Paul Cuffee's legacy is enshrined in the Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it lives on in his descendants, both Asante and Wampanoag. It is a reminder of both our peoples' legacies of surviving (and thriving) even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. It is an inspiration for future generations of our children, who can and will build on his achievements in places and ways yet undreamed, and perhaps most of all, who can be who they are.

Copyright Ajijaakwe, 2016; all rights reserved. Note: All content on this blog, except where otherwise indicated, is copyright Aji and/or Wings, 2014; all rights reserved.

Note: This was first posted at Daily Kos on February 28, 2013. It seems worth reposting here for Black History Month this year.

Quite an interesting story. One thing that has always fascinated me about the black/Indian experience in America is that in some places, men and women who were obviously black chose to be Indians and vice versa. Some of this was merely personal choice, but for many it was done to protect themselves from racist responses. While racism was directed at both blacks and Indians, of course, depending on the location, it could be considerably worse for a black or for an Indian than if they chose to self-identify as one or the other. There were also Indians, as in Virginia in the 1930s, who were forced to identify as black as a means of placing them under Jim Crow laws. And then, of course, there was the sign-up for the Dawes (and other) Rolls of Indians in the 1890s-1906, when tens of thousands of Indians were labeled white (even as their sisters and brothers by blood were classified as Indian, based purely on appearance (or the whim of the classifier). For them, being who they were became extremely difficult. An interesting book on this subject is Confounding the Color Line: The Indian-Black Experience in North America, and anthology published in 2002.

ReplyDelete